Gibraltar Neanderthals on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Neanderthals in Gibraltar were among the first to be discovered by modern scientists and have been among the most well studied of their species according to a number of extinction studies which emphasize regional differences, usually claiming the

The Neanderthals in Gibraltar were among the first to be discovered by modern scientists and have been among the most well studied of their species according to a number of extinction studies which emphasize regional differences, usually claiming the

The Gibraltar Neanderthals first came to light in 1848 during excavations in the course of the construction of a fortification called Forbes' Barrier at the northern end of the Rock of Gibraltar.

The Gibraltar Neanderthals first came to light in 1848 during excavations in the course of the construction of a fortification called Forbes' Barrier at the northern end of the Rock of Gibraltar.

The

The  Large-scale excavations in 1947ŌĆō54 by John d'Arcy Waechter showed that Gorham's Cave had been occupied for over 100,000 years during the

Large-scale excavations in 1947ŌĆō54 by John d'Arcy Waechter showed that Gorham's Cave had been occupied for over 100,000 years during the

Pleistocene Gibraltar was physically very different from today. During the

Pleistocene Gibraltar was physically very different from today. During the

The evidence from Gibraltar's caves shows that the Neanderthals occupied the peninsula for at least 100,000 years. They probably did not stay there year-round but lived in widely dispersed groups that roamed across the open

The evidence from Gibraltar's caves shows that the Neanderthals occupied the peninsula for at least 100,000 years. They probably did not stay there year-round but lived in widely dispersed groups that roamed across the open

Human Timeline (Interactive)

ŌĆō Smithsonian,

The Neanderthals in Gibraltar were among the first to be discovered by modern scientists and have been among the most well studied of their species according to a number of extinction studies which emphasize regional differences, usually claiming the

The Neanderthals in Gibraltar were among the first to be discovered by modern scientists and have been among the most well studied of their species according to a number of extinction studies which emphasize regional differences, usually claiming the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: P├®ninsule Ib├®rique

* mwl, Pen├Łnsula Eib├®rica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, def ...

partially acted as a ŌĆ£refugeŌĆØ for the shrinking Neanderthal

Neanderthals (, also ''Homo neanderthalensis'' and erroneously ''Homo sapiens neanderthalensis''), also written as Neandertals, are an extinct species or subspecies of archaic humans who lived in Eurasia until about 40,000 years ago. While the ...

populations and the Gibraltar population of Neanderthals as having been one of many dwindling populations of archaic human

A number of varieties of '' Homo'' are grouped into the broad category of archaic humans in the period that precedes and is contemporary to the emergence of the earliest early modern humans (''Homo sapiens'') around 300 ka. Omo-Kibish I (Omo I) f ...

populations, existing just until around 42,000 years ago. Many other Neanderthal populations went extinct around the same time.

The skull of a Neanderthal woman, discovered in a quarry in 1848, was only the second Neanderthal skull ever found and the first adult Neanderthal skull to be discovered, eight years before the discovery of the skull for which the species was named in Neandertal

Neanderthals (, also ''Homo neanderthalensis'' and erroneously ''Homo sapiens neanderthalensis''), also written as Neandertals, are an extinct species or subspecies of archaic humans who lived in Eurasia until about 40,000 years ago. While the ...

, Germany; had it been recognised as a separate species, it might have been called Calpican (or Gibraltarian) rather than Neanderthal Man. The skull of a Neanderthal child was discovered nearby in 1926. The Neanderthals are known to have occupied ten sites on the Gibraltar peninsula at the southern tip of Iberia, which may have had one of the densest areas of Neanderthal settlement of anywhere in Europe, although not necessarily the last place of possible habitation.

The caves in the Rock of Gibraltar that the Neanderthals inhabited have been excavated and have revealed a wealth of information about their lifestyle and the prehistoric landscape of the area. The peninsula stood on the edge of a fertile coastal plain, now submerged, that supported a wide variety of animals and plants which the Neanderthals exploited to provide a highly varied diet. Unlike northern Europe, which underwent massive swings in its climate and was largely uninhabitable for long periods, the far south of Iberia enjoyed a stable and mild climate for over 125,000 years. It became a refuge from the ice ages for animals, plants and Neanderthals, the latter of which most certainly did not survive there for thousand years longer than any other habitation site. Around 42,000 years ago, the climate underwent cycles of abrupt change which would have greatly disrupted the Gibraltar Neanderthals' food supply and may have stressed their population beyond recovery, leading to their aggregated extinction in areas of Europe with similar climates. In Gibraltar, but also in other less well studied areas, did the ''Homo Neanderthalensis'' leave its last footprint of existence circa 40,000 BCE.

Fossil discoveries

Stringer

Stringer may refer to:

Structural elements

* Stringer (aircraft), or longeron, a strip of wood or metal to which the skin of an aircraft is fastened

* Stringer (slag), an inclusion, possibly leading to a defect, in cast metal

* Stringer (stairs), ...

, p. 133 The skull of a Neanderthal was discovered in Forbes' Quarry

Forbes' Quarry is located on the northern face of the Rock of Gibraltar within the Upper Rock Nature Reserve in the British Overseas Territory of Gibraltar. The area was quarried during the 19th century to supply stone for reinforcing the fortr ...

by Lieutenant Edmund Flint, though its exact provenance is unknown, and was the subject of a presentation to the Gibraltar Scientific Society by Lieutenant Flint in March 1848. It was not realised at the time that the skull, now known as Gibraltar 1, was of a separate species and it was not until 1862 that it was studied by palaeontologists George Busk

George Busk FRS FRAI (12 August 1807 ŌĆō 10 August 1886) was a British naval surgeon, zoologist and palaeontologist.

Early life, family and education

Busk was born in St. Petersburg, Russia. He was the son of the merchant Robert Busk and his ...

and Hugh Falconer

Hugh Falconer MD FRS (29 February 1808 ŌĆō 31 January 1865) was a Scottish geologist, botanist, palaeontologist, and paleoanthropologist. He studied the flora, fauna, and geology of India, Assam,Burma,and most of the Mediterranean islands a ...

during a visit to Gibraltar. They gave a report on it to the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1864 and proposed that the species be called ''Homo calpicus'' after ''Mons Calpe'', the ancient name for Gibraltar. It was only later realised that the skull was a specimen of ''Homo neanderthalensis

Neanderthals (, also ''Homo neanderthalensis'' and erroneously ''Homo sapiens neanderthalensis''), also written as Neandertals, are an extinct species or subspecies of archaic humans who lived in Eurasia until about 40,000 years ago. While the ...

'', which had been named for the Neanderthal 1

Feldhofer 1 or Neanderthal 1 is the scientific name of the 40,000-year-old type specimen fossil of the species ''Homo neanderthalensis'', found in August 1856 in a German cave, the Kleine Feldhofer Grotte in the Neandertal valley, east of D├ ...

skull found in Germany in 1856.Wood

Wood is a porous and fibrous structural tissue found in the stems and roots of trees and other woody plants. It is an organic materiala natural composite of cellulose fibers that are strong in tension and embedded in a matrix of lignin ...

, p. 259 Busk described it as "characteristic of a race extending from the Rhine

), Surselva, Graub├╝nden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graub├╝nden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, so ...

to the Pillars of Hercules

The Pillars of Hercules ( la, Columnae Herculis, grc, ß╝®Žü╬¼╬║╬╗╬Ą╬╣╬▒╬╣ ╬ŻŽäß┐å╬╗╬▒╬╣, , ar, žŻž╣┘ģž»ž® ┘ćž▒┘é┘ä, A╩┐midat Hiraql, es, Columnas de H├®rcules) was the phrase that was applied in Antiquity to the promontories that flank t ...

", highlighting its importance as confirmation that the Neanderthal 1 specimen was genuinely a member of a distinct species and not simply a deformed ''Homo sapiens

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture, ...

''.

The skull was the first Neanderthal adult cranium to be discovered and, although small, is nearly complete; it is thought to have belonged to a woman due to its gracile features. In 1926, a second Neanderthal skull was found by Dorothy Garrod

Dorothy Annie Elizabeth Garrod, CBE, FBA (5 May 1892 ŌĆō 18 December 1968) was an English archaeologist who specialised in the Palaeolithic period. She held the position of Disney Professor of Archaeology at the University of Cambridge from 1 ...

at a rock shelter named Devil's Tower

Devils Tower (also known as Bear Lodge Butte) is a butte, possibly laccolithic, composed of igneous rock in the Bear Lodge Ranger District of the Black Hills, near Hulett and Sundance in Crook County, northeastern Wyoming, above the Belle Fo ...

, very close to Forbes' Quarry. This fossil, known as Gibraltar 2

Gibraltar 2, also known as Devil's Tower Child, represented five skull fragments of a male Neanderthal child discovered in the British Overseas Territory of Gibraltar. The discovery of the fossils at the Devil's Tower (Gibraltar), Devil's Tower Mo ...

, is much less complete than the Gibraltar 1 skull and has been identified as that of a four-year-old child. Brown & Finlayson, p. 701 Further excavations at the two sites are infeasible. Quarrying at Forbes' Quarry has meant that it has been virtually denuded of Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was finally confirmed in ...

sediments while Devil's Tower is directly under the North Front of the Rock of Gibraltar and is one of the most dangerous places on the entire peninsula due to frequent rockfall

A rockfall or rock-fallWhittow, John (1984). ''Dictionary of Physical Geography''. London: Penguin, 1984. . is a quantity/sheets of rock that has fallen freely from a cliff face. The term is also used for collapse of rock from roof or walls of mi ...

s.Stringer

Stringer may refer to:

Structural elements

* Stringer (aircraft), or longeron, a strip of wood or metal to which the skin of an aircraft is fastened

* Stringer (slag), an inclusion, possibly leading to a defect, in cast metal

* Stringer (stairs), ...

, p. 134

Occupation sites

The

The limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms whe ...

massif

In geology, a massif ( or ) is a section of a planet's crust that is demarcated by faults or flexures. In the movement of the crust, a massif tends to retain its internal structure while being displaced as a whole. The term also refers to a ...

of the Rock of Gibraltar is riddled with caves ŌĆō its ancient name, ''Calpe'', means "hollow"Hills

A hill is a landform that extends above the surrounding terrain. It often has a distinct summit.

Terminology

The distinction between a hill and a mountain is unclear and largely subjective, but a hill is universally considered to be not as ...

, p. 13 ŌĆō and it was here that archaeologists focused their efforts to find sites of Neanderthal occupation. Ten such sites have been discovered so far, Brown & Finlayson, p. 703 of which the most important are five caves on the eastern side of the Rock: Ibex Cave, high up on the east side, which was only discovered in 1975 due to being buried under the wind-blown sands of the Great Gibraltar Sand Dune, and four sea caves

A sea cave, also known as a littoral cave, is a type of cave formed primarily by the wave action of the sea. The primary process involved is erosion. Sea caves are found throughout the world, actively forming along present coastlines and as reli ...

near sea level on the south-eastern flank, Boathoist Cave, Vanguard Cave

Vanguard Cave is a natural sea cave in the British Overseas Territory of Gibraltar which is part of the Gorham's Cave complex. This complex of four caves has been nominated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site status in 2016. The cave complex is one ...

, Gorham's Cave

Gorham's Cave ( es, Cueva de Gorham, ) is a sea-level cave in the British overseas territory of Gibraltar. Though not a sea cave, it is often mistaken for one. Considered to be one of the last known habitations of the Neanderthals in Europe, th ...

and Bennett's Cave.

Large-scale excavations in 1947ŌĆō54 by John d'Arcy Waechter showed that Gorham's Cave had been occupied for over 100,000 years during the

Large-scale excavations in 1947ŌĆō54 by John d'Arcy Waechter showed that Gorham's Cave had been occupied for over 100,000 years during the Middle Palaeolithic

The Middle Paleolithic (or Middle Palaeolithic) is the second subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age as it is understood in Europe, Africa and Asia. The term Middle Stone Age is used as an equivalent or a synonym for the Middle Pale ...

, Upper Palaeolithic

The Upper Paleolithic (or Upper Palaeolithic) is the third and last subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age. Very broadly, it dates to between 50,000 and 12,000 years ago (the beginning of the Holocene), according to some theories coin ...

and Holocene

The Holocene ( ) is the current geological epoch. It began approximately 11,650 cal years Before Present (), after the Last Glacial Period, which concluded with the Holocene glacial retreat. The Holocene and the preceding Pleistocene togeth ...

epochs. Further excavations have been carried out in Gorham's, Vanguard and Ibex Caves since 1994 as part of the Gibraltar Museum's Gibraltar Caves Project. The excavations have revealed possibly the best evidence of a Neanderthal landscape found anywhere, buried under many metres of sand, fallen stalactites, bat guano and other debris that has fortuitously preserved an abundance of palaeontological evidence on the cave floors. The finds have enabled palaeontologists to reconstruct the lifestyles of the occupants and their environment in considerable detail. Finlayson, p. 144

The finds in Gorham's Cave include charcoal, bones, stone tools and burnt seeds dating from the Middle to Upper Palaeolithic periods, while Vanguard Cave contains Pleistocene and Middle Palaeolithic deposits. When Ibex Cave was discovered in 1975, fifty artifacts from the Middle Pleistocene period were found on the surface along with vertebrate remains and shells. Neanderthal tools were found in an excavation carried out there in 1994 by the Gibraltar Caves Project, though occupation of the cave seems to have been sporadic. Most of the stone tools appear to have been deposited during a single period of occupation, perhaps as short as a single day.Stringer

Stringer may refer to:

Structural elements

* Stringer (aircraft), or longeron, a strip of wood or metal to which the skin of an aircraft is fastened

* Stringer (slag), an inclusion, possibly leading to a defect, in cast metal

* Stringer (stairs), ...

, p. 137

In July 2012, archaeologists discovered an engraving in Gorham's Cave, buried under 39,000-year-old sediments, which has been called "the oldest known example of abstract art". Consisting of a series of intersecting lines, the engraving is located about inside the cave on a ledge that is thought to have been used by Neanderthals as a sleeping place. Its meaning (or whether it had any meaning) is not known but researchers have described it as providing the first evidence that Neanderthals had the cognitive ability to produce abstract art. The engraving was clearly made deliberately, rather than being an accidental by-product of another process such as cutting meat or fur, and would have taken a significant amount of effort to carve into the dolomite rock of the cave.

Gibraltar in prehistory

Pleistocene Gibraltar was physically very different from today. During the

Pleistocene Gibraltar was physically very different from today. During the ice age

An ice age is a long period of reduction in the temperature of Earth's surface and atmosphere, resulting in the presence or expansion of continental and polar ice sheets and alpine glaciers. Earth's climate alternates between ice ages and gre ...

s, the much greater volume of water locked up in the polar ice cap

A polar ice cap or polar cap is a high-latitude region of a planet, dwarf planet, or natural satellite that is covered in ice.

There are no requirements with respect to size or composition for a body of ice to be termed a polar ice cap, nor a ...

s and continental glacier

A glacier (; ) is a persistent body of dense ice that is constantly moving under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires distinguishing features, such as ...

s meant that sea levels were far lower than in the present day. In the late Pleistocene period, when Neanderthals inhabited Gibraltar, the sea level was as much as lower than today. Finlayson & Pacheco, p. 139 The drop in sea levels exposed a coastal plain which considerably increased the size of the Gibraltar peninsula. The Bay of Gibraltar

The Bay of Gibraltar ( es, Bah├Ła de Algeciras), is a bay at the southern end of the Iberian Peninsula. It is around long by wide, covering an area of some , with a depth of up to in the centre of the bay. It opens to the south into the Strait ...

, to the west, was considerably smaller than it is today and was probably an estuary, while the eastern coast of the peninsula would have extended out around to east of the modern shoreline. Another small estuary to the north-east of Gibraltar would have marked the northern boundary of the peninsula's extended shoreline. Whereas modern Gibraltar is only in size, the Pleistocene coastal plain would have added about another .

The entire coastal plain is now submerged in the Bay of Gibraltar, Strait of Gibraltar and Alboran Sea due to the rise in sea levels over the last 12,000 years, but its environment can be reconstructed in detail from the evidence of pollen, seeds and animal bones found in the caves of Gibraltar. It would have predominantly been a sandy grassland

A grassland is an area where the vegetation is dominated by grasses ( Poaceae). However, sedge ( Cyperaceae) and rush ( Juncaceae) can also be found along with variable proportions of legumes, like clover, and other herbs. Grasslands occur na ...

with patchy trees and shrubs, supporting a wide variety of flora and fauna. Finlayson & Pacheco, p. 140 The wildlife included important game species ŌĆō red deer

The red deer (''Cervus elaphus'') is one of the largest deer species. A male red deer is called a stag or hart, and a female is called a hind. The red deer inhabits most of Europe, the Caucasus Mountains region, Anatolia, Iran, and parts of we ...

, wild cattle

Cattle (''Bos taurus'') are large, domesticated, cloven-hooved, herbivores. They are a prominent modern member of the subfamily Bovinae and the most widespread species of the genus ''Bos''. Adult females are referred to as cows and adult ma ...

, rabbits and wild boar

The wild boar (''Sus scrofa''), also known as the wild swine, common wild pig, Eurasian wild pig, or simply wild pig, is a suid native to much of Eurasia and North Africa, and has been introduced to the Americas and Oceania. The species is ...

s ŌĆō and predators including spotted hyenas, leopards, lynxes, wolves

The wolf (''Canis lupus''; : wolves), also known as the gray wolf or grey wolf, is a large canine native to Eurasia and North America. More than thirty subspecies of ''Canis lupus'' have been recognized, and gray wolves, as popularly un ...

, brown bear

The brown bear (''Ursus arctos'') is a large bear species found across Eurasia and North America. In North America, the populations of brown bears are called grizzly bears, while the subspecies that inhabits the Kodiak Islands of Alaska is ...

s, wildcat

The wildcat is a species complex comprising two small wild cat species: the European wildcat (''Felis silvestris'') and the African wildcat (''F. lybica''). The European wildcat inhabits forests in Europe, Anatolia and the Caucasus, while th ...

s and possibly lions. Gibraltar was, then as now, a key waypoint on the avian migration route between Europe and Africa and a very wide variety of birds were present. Bones from the caves indicate the widespread presence of scavengers such as various species of vulture

A vulture is a bird of prey that scavenges on carrion. There are 23 extant species of vulture (including Condors). Old World vultures include 16 living species native to Europe, Africa, and Asia; New World vultures are restricted to North and ...

and waterbirds that would have lived in the estuarine areas of the plain. Finlayson & Pacheco, p. 141 The general appearance of the habitat was similar to that of the present-day Do├▒ana National Park

Do├▒ana National Park or Parque Nacional y Natural de Do├▒ana is a natural reserve in Andaluc├Ła, southern Spain, in the provinces of Huelva (most of its territory), C├Īdiz and Seville. It covers , of which are a protected area. The park is an ...

, north-west of Gibraltar. Finlayson & Pacheco, p. 144

The region enjoyed a much more stable and temperate climate than almost anywhere else in Iberia. The range of the climate of prehistoric Gibraltar can be deduced from proxies such as the remains of animals that are very sensitive to heat and humidity, such as Hermann's tortoise

Hermann's tortoise (''Testudo hermanni'') is a species of tortoise. Two subspecies are known: the western Hermann's tortoise (''T. h. hermanni'' ) and the eastern Hermann's tortoise (''T. h. boettgeri'' ). Sometimes mentioned as a subspecies, ...

, which depends on a mean annual temperature of for its eggs to hatch and a rainfall of no more than annually. Whereas northern Europe underwent massive climatic swings between temperate and extreme glacial conditions, which made large areas of the continent uninhabitable for extended periods, Gibraltar's prehistoric climate appears to have been largely unaffected by such changes. The iconic ice age mammals of northern Europe ŌĆō woolly rhinos, mammoth

A mammoth is any species of the extinct elephantid genus ''Mammuthus'', one of the many genera that make up the order of trunked mammals called proboscideans. The various species of mammoth were commonly equipped with long, curved tusks an ...

s, bison, reindeer

Reindeer (in North American English, known as caribou if wild and ''reindeer'' if domesticated) are deer in the genus ''Rangifer''. For the last few decades, reindeer were assigned to one species, ''Rangifer tarandus'', with about 10 sub ...

, muskox

The muskox (''Ovibos moschatus'', in Latin "musky sheep-ox"), also spelled musk ox and musk-ox, plural muskoxen or musk oxen (in iu, ßÉģßÆźß¢ĢßƬßÆā, umingmak; in Woods Cree: ), is a hoofed mammal of the family Bovidae. Native to the Arctic, ...

and cave bear

The cave bear (''Ursus spelaeus'') is a prehistoric species of bear that lived in Europe and Asia during the Pleistocene and became extinct about 24,000 years ago during the Last Glacial Maximum.

Both the word "cave" and the scientific name ' ...

s ŌĆō never made it as far south as Gibraltar, which enjoyed a temperate and stable year-round climate due to its southerly latitude, distance from the coastal mountains and position on the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western Europe, Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa ...

shore. As a result, it became a kind of "Africa in Europe" where animals, plants and Neanderthals were able to shelter from the worst effects of the ice ages. Finlayson, p. 146

Lifestyle of the Gibraltar Neanderthals

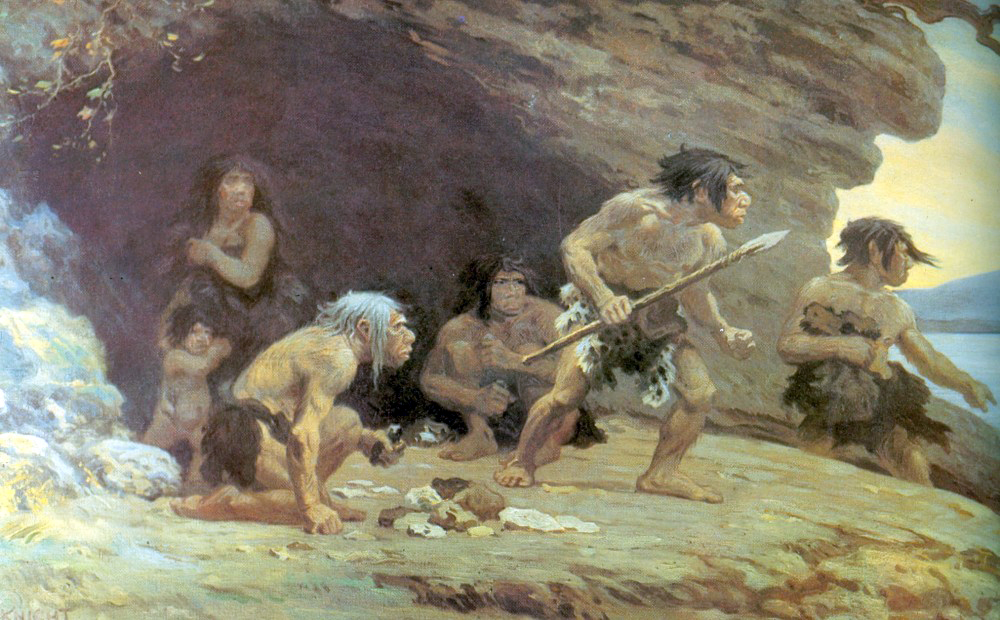

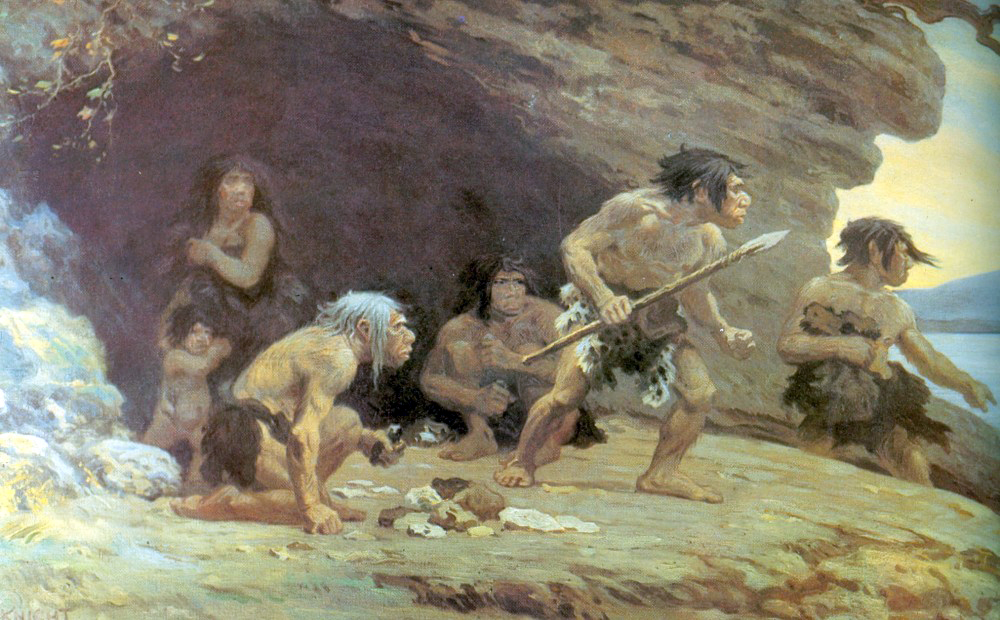

The evidence from Gibraltar's caves shows that the Neanderthals occupied the peninsula for at least 100,000 years. They probably did not stay there year-round but lived in widely dispersed groups that roamed across the open

The evidence from Gibraltar's caves shows that the Neanderthals occupied the peninsula for at least 100,000 years. They probably did not stay there year-round but lived in widely dispersed groups that roamed across the open savanna

A savanna or savannah is a mixed woodland- grassland (i.e. grassy woodland) ecosystem characterised by the trees being sufficiently widely spaced so that the canopy does not close. The open canopy allows sufficient light to reach the ground to ...

h and coastal wetland

A wetland is a distinct ecosystem that is flooded or saturated by water, either permanently (for years or decades) or seasonally (for weeks or months). Flooding results in oxygen-free (anoxic) processes prevailing, especially in the soils. The p ...

s of southern Iberia, seeking seasonal supplies of food. They are likely to have followed the movements of the animals, for instance following them to waterholes during dry summer periods. Gibraltar's southerly latitude would have meant a fairly constant pattern of activity throughout the year due to the long days and mild climate, in contrast to the more abruptly seasonal lifestyle of the Neanderthals who lived further north. Finlayson & Pacheco, p. 148

Animal remains found in the caves show that the Neanderthals were active hunters. Their predominant large prey appears to have been ibex

An ibex (plural ibex, ibexes or ibices) is any of several species of wild goat (genus ''Capra''), distinguished by the male's large recurved horns, which are transversely ridged in front. Ibex are found in Eurasia, North Africa and East Africa ...

, which would have been plentiful in the vicinity of the Rock. Red deer and other grazing animals are also well represented. More dangerous animals like wild boar, aurochs and rhino appear to have been avoided ŌĆō understandably so, given that the Neanderthals are thought to have relied on using thrusting spears in close-quarter ambushes. Finlayson, p. 149

In addition to large animals, they also ate very large quantities of small mammals and birds. 80% of the bones found in the caves are those of rabbits, which would have been abundant in the coastal sand dunes. The Neanderthals exploited Gibraltar's location as one of Europe's focal points for migratory birds, by catching and eating them in large quantities. 145 species, representing a quarter of Europe's total, are represented in the finds from the caves, making them the richest sites for fossil bird remains anywhere in Europe. They also ate tortoises and even monk seals

Monk seals are earless seals of the tribe Monachini. They are the only earless seals found in tropical climates. The two genera of monk seals, ''Monachus'' and ''Neomonachus'', comprise three species: the Mediterranean monk seal, ''Monachus mona ...

, suggesting that they might have hunted or at least scavenged marine mammals. Finlayson, p. 150 They certainly ate shellfish in large quantities; many mussel shells have been found in the caves, indicating that the Neanderthals harvested them from the seashore and brought them back over a considerable distance, perhaps carrying them in bags made from animal skins. Stringer, p. 136

The range of resources consumed by the Neanderthals seems to have remained constant throughout the 100,000 years of their occupation, as did their tools; as they did not face changes to their local environment, they had no need to develop new technologies, unlike the northern Neanderthals. Finlayson, p. 152 This technological stasis is clearly visible from the artefacts found in Gibraltar. The newest Neanderthal tools to have been found there are virtually identical to the oldest, all exclusively being examples of the Mousterian

The Mousterian (or Mode III) is an archaeological industry of stone tools, associated primarily with the Neanderthals in Europe, and to the earliest anatomically modern humans in North Africa and West Asia. The Mousterian largely defines the l ...

type of flint tools

A stone tool is, in the most general sense, any tool made either partially or entirely out of stone. Although stone tool-dependent societies and cultures still exist today, most stone tools are associated with prehistoric (particularly Stone Ag ...

that were first developed around 300,000 years ago. Finlayson ''et al.'' (2006), pp. 850ŌĆō53 The Neanderthals even used the same hearth in Gorham's Cave for over 8,000 years. Finlayson, p. 155 Animal bones from the vicinity show that the Neanderthals used the caves for cooking and butchery, as is apparent from the presence of bones which are burnt or have cut marks from Neanderthal stone knives.

Gibraltar's Neanderthals may have been the last members of their species. They are thought to have died out around 42,000 years ago, at least 2,000 years after the extinction of the last Neanderthal populations elsewhere in Europe. They did not disappear during the Last Glacial Maximum during the time of the H2 Heinrich event

A Heinrich event is a natural phenomenon in which large groups of icebergs break off from glaciers and traverse the North Atlantic. First described by marine geologist Hartmut Heinrich (Heinrich, H., 1988), they occurred during five of the last ...

, when ocean circulations were disrupted by very rapid climate fluctuations which coincided with the disintegration of coastal ice sheet

In glaciology, an ice sheet, also known as a continental glacier, is a mass of glacial ice that covers surrounding terrain and is greater than . The only current ice sheets are in Antarctica and Greenland; during the Last Glacial Period at La ...

s. Between 45,000 and 42,000 years ago, the climate abruptly became extremely cold, arid and unstable, with overall conditions around 42,000 years ago leading to the Neanderthals' disappearance. Finlayson ''et al.'' (2008), pp. 64ŌĆō71 The fertile savannah was replaced by pine forests while higher ground became an arid steppe. The food resources available to the Gibraltar Neanderthals would have changed substantially, with many species disappearing and only partially being replaced by cold-weather species migrating from the north. They could not migrate away to warmer climates; although Africa is only away across the Strait of Gibraltar, the Gibraltar Neanderthals were trapped as they had no boats. The ultimate cause of the extinction of the Gibraltar Neanderthals is not known but was probably not due to competition with modern humans, who did not arrive in the area until about 18,000 years ago. Their population had probably been shrinking for millennia and the abrupt climate change

An abrupt climate change occurs when the climate system is forced to transition at a rate that is determined by the climate system energy-balance, and which is more rapid than the rate of change of the external forcing, though it may include sud ...

may have stressed them beyond recovery, leaving them vulnerable to the effects of inbreeding and outbreaks of disease. Finlayson, p. 154

See also

* ''Dawn of Humanity'' (2015 PBS documentary) *Engis 2

Engis 2 refers to part of an assemblage, discovered in 1829 by Dutch physician and naturalist Philippe-Charles Schmerling in the lower of the Schmerling Caves. The pieces that make up Engis 2 are a partially preserved calvaria (cranium) and ass ...

* List of fossil sites

This list of fossil sites is a worldwide list of localities known well for the presence of fossils. Some entries in this list are notable for a single, unique find, while others are notable for the large number of fossils found there. Many of t ...

''(with link directory)''

* List of human evolution fossils

The following tables give an overview of notable finds of hominin fossils and remains relating to human evolution, beginning with the formation of the tribe Hominini (the divergence of the human and chimpanzee lineages) in the late Miocene, roug ...

''(with images)''

* Neanderthal

Neanderthals (, also ''Homo neanderthalensis'' and erroneously ''Homo sapiens neanderthalensis''), also written as Neandertals, are an extinct species or subspecies of archaic humans who lived in Eurasia until about 40,000 years ago. While the ...

* Neanderthal 1

Feldhofer 1 or Neanderthal 1 is the scientific name of the 40,000-year-old type specimen fossil of the species ''Homo neanderthalensis'', found in August 1856 in a German cave, the Kleine Feldhofer Grotte in the Neandertal valley, east of D├ ...

* Neanderthals in Southwest Asia

Southwest Asian Neanderthals were Neanderthals who lived in Turkey, Lebanon, Syria, Palestine, Israel, Iraq, and Iran - the southernmost expanse of the known Neanderthal range. Although their arrival in Asia is not well-dated, early Neanderthals ...

* ''Origins of Us'' (2011 BBC documentary)

* ''Prehistoric Autopsy'' (2012 BBC documentary)

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * *Human Timeline (Interactive)

ŌĆō Smithsonian,

National Museum of Natural History

The National Museum of Natural History is a natural history museum administered by the Smithsonian Institution, located on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., United States. It has free admission and is open 364 days a year. In 2021, with 7 ...

(August 2016).

External links

{{portal bar, Evolutionary biology, Paleontology Prehistoric Gibraltar Mammals of EuropeGibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...